La correlación entre términos prejuiciados y crímenes de odio hacia este y sureste asiáticos americanos durante la pandemia del COVID-19

Mariely S. Gómez Vázquez

Departamento de Psicología

Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, UPR RP

Recibido: 17/09/2025; Revisado: 21/11/2025; Aceptado: 25/11/2025

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the role of media in shaping perceptions and fueling prejudice. This study explored the relationship between prejudiced terms in news headlines and the rise of hate crimes against East and Southeast Asian American communities during the pandemic’s early months. Guided by psychological frameworks including selective attention, confirmation bias, and social identity theory, the research examined monthly headline data alongside hate crime reports. Results indicated a strong correlation among the selected variables. At the same time, limitations include the lack of detailed ethnic categorization in the FBI Crime Data Explorer, highlighting the need for greater accuracy and transparency.

Keywords: COVID-19, prejudice, framing theory, confirmation bias, hate crimes

Resumen

La pandemia de covid-19 evidenció un énfasis en el cambio de percepción y en el aumento del prejuicio, especialmente en poblaciones del este y del sudeste asiáticos. Utilizando un marco teórico psicológico —atención selectiva, sesgo de confirmación e identidad social—, se realizó un estudio de correlación entre los términos prejuiciosos empleados en los titulares de noticias en línea y la totalidad de los crímenes de odio reportados entre marzo y julio de 2020. Los resultados evidenciaron una correlación significativa, aunque las limitaciones indican una falta de diferenciación entre los grupos étnicos que componen la categoría ‘Anti-Asiático’ en el ‘Crime Data Explorer’ del FBI.

Palabras clave: covid-19, prejuicio, teoría del marco, sesgo de confirmación, crímenes de odio

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic served as a historical event that demonstrated the rapid spread of coronavirus, the representation of the spread through news media outlets, and a significant increase in hate crimes toward different communities that make up the Asian American population in the United States. With more than 2.5 million confirmed cases worldwide in April 2020 (Stechemesser et. al., 2020), national news outlets became the primary source of information for 56% of U.S. adults (Mitchell et al., 2020). The said article conducted, where about 61% of U.S. Adults were paying equal attention to local and national news, 40% were staying up to date with national health organizations, like the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), while a third of the participants were following the actions and statements of federal government officials. Taking this into consideration, it is likely that they have followed not only the words and opinions of politicians and government officials, but also those of President Donald J. Trump. By contradicting the World Health Organization’s (WHO) statement (Walters et al., 2020) on COVID-19 mortality rates (Keith & Romo, 2020), Trump gained traction through his presidential position, which positioned him as a significant figure of authority. Furthermore, the Trump administration was adamant that the virus originated in Wuhan, China, and insisted that the Chinese government was to blame for its spread (Lederman, 2020). Mike Pompeo, then Secretary of State, also emphasized the importance of remembering COVID-19’s origins in China, referring to the pandemic as “the Wuhan virus”. Naming a disease by its place of origin is nothing new; Ittefaq et. al. (2022) state that said strategies are meant to justify racist behavior against minorities, referring to the COVID-19 pandemic as a threat, unlike the Chinese media. By March 24, 2020, Chinese Americans were facing a rise in verbal and physical attacks, along with other Asian Americans with families from Korea, the Philippines, and Myanmar, among others, being lumped together under a prejudiced perspective (Tavernise & Oppel, 2020). Sungil et al. (2023) also highlighted the spike in hate crimes toward Asian Americans after March 16, 2020, exploring their connections to the “blaming labels” made by government officials. Although there was a confirmed rise in these incidents, President Trump doubled down on the term ‘Chinese virus’, emphasizing the fact that “the virus comes from China”; even though he has great love for all of the people in the United States, he stated he wanted to “be accurate” when talking about the coronavirus pandemic (Yam, 2020). The article stated that the president justified his new label for the virus as a means of preventing misinformation, even though reports on racist incidents were on the rise soon after.

Hate crimes are often violent crimes committed under a biased perspective against people or groups with specific characteristics (U.S. Department of Justice, 2024). The biases presented in said crimes are based on race, color, religion, national origin, sexual orientation, gender, and disability, among others. According to the U.S. Department of Justice, hate crime victims include the victim’s immediate target and others like them, meaning they affect families and entire communities. Under the scope of this study, hate crimes towards two groups that make up the Asian American population (East and Southeast Asians) will be examined in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic.

According to the American Psychological Association (n.d.), prejudice is a negative attitude toward another person or group formed before any experience with that person or group; it can include an affective component — such as anger and hatred — that can manifest in discriminatory behavior. An example of said behaviors can be using the terms used for the COVID-19 pandemic that imply a distortion of information and target the Asian American population in the U.S. due to the spread of the virus.

Incidents like this led to an important question: Is there a direct connection between these prejudiced terms used to name the COVID-19 pandemic and the spike in hate crimes toward East and Southeast Asian Americans? This study aims to determine if there is a correlation between prejudiced terms seen in news headlines and hate crime incidents toward the East and Southeast Asian American communities. This project hypothesizes that, if a correlation exists between the chosen variables, it will be positive. Three terms were chosen to serve as variables for this project and will be discussed in the following sections.

Existing Literature

The literature explored in the University of North Carolina (UNC) Libraries database demonstrated a rise in hate speech and hate crimes as well as their ties to the spread of COVID-19, utilizing social media and news outlets as sources. The representation of the illness as a threat through online news outlets, combined with the spread of social media threads promoting prejudiced behavior, emphasized the alleged origin of the virus: Wuhan, China. With different approaches and objects of study, hate crimes, racist behavior in media sources, and discrimination toward Asian Americans were present consistently throughout the sources, illustrating the possibility of these dimensions being connected. However, there were no studies that emphasized the use of prejudiced terms that referred to the COVID-19 pandemic and their association with hate crime incidents, at least not with the ones that were chosen for this project. Furthermore, the representation of the pandemic through media sources and hate crime incidents, as well as prejudiced behavior and discrimination, were explored through a causal relationship. One study explored the potential connection between the “blaming labels” issued by government officials and the significant surge in hate crimes that occurred on and after March 16, 2020, but did not produce evidence through a correlational method (Sungil et al., 2023). Most of the literature revealed hate crime incidents toward Chinese Americans or Asian Americans in general, which granted an incomplete scope for the chosen object of study.

Theoretical Framework

The conceptual framework for this study relies strongly on the framing theory (Pan & Kosicki, 1993), which emphasizes the correlational relationship between the chosen variables. Said theory can be observed through sociological and psychological conceptions, which imply cognitive processes, perceptions, and “frames” that enable individuals “to locate, perceive, identify and label” (Goffman, 1974 in Pan and Kosicki, 1993, p. 56). This theory posits that the creation of such frames serves as a strategy for processing news discourse and is significant in evaluating social groups different from one’s own. Different themes that frame a particular event give it meaning and develop a structure, intertwined with an individual’s own thoughts. That being said, it is essential to emphasize that the prejudiced terms are not being observed as the cause for the hate crime count that was extracted from this study, instead that they interact with one another during the same period of time because of how public reaction is tied to how different events are framed through the media and vice versa.

The conceptual framework of this study also relies on the branch of cognitive psychology, specifically, the phenomenon of selective attention. Selective attention involves focusing our mental resources on a single task rather than multiple tasks (Galotti, 2018). In the context of this study, one task can be the key term used when news sources refer to the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, the most searched terms were related to COVID-19, especially in countries with higher case numbers (Rovetta & Srikanth Bhagavathula, 2020). The phenomenon of selective attention can be applied to the ‘keywords’ found in the selected news media headlines because it raises the possibility of the reader focusing their attentiveness on a key term instead of the headline as a whole, and, therefore, could lose context of the article in general. Additionally, key terms represent the main concepts of the topic in question (University of Houston Libraries, n.d.). Meyer (2022) states that keywords are useful as a media tool to reach as many consumers as possible and to “create buzz,” demonstrating their usefulness — positively and negatively, as shown in this project — when explaining an event as significant as the COVID-19 pandemic.

Confirmation bias can play a key role when intertwined with the framing theory, if the individual already feels prejudice towards a certain population, deeming them inferior or the ‘out-group’ (Stets & Burke, 2000, p. 120), and observing them in a negative light. Because of the nature of this project, observing the association of the selected variables is essential, specifically hate crimes, given that, in extreme cases, prejudice could lead to an ‘us-versus-them’ mentality (McWhorter, 2025).

To tie these concepts together, the framing theory and confirmation bias present a reality created by the individual, in which different representations of events can play a role in shaping it. Selective attention amplifies the perception of and focus on some frames, which become subject to the preexisting beliefs of those who see them. When media sources — in this case, online newspapers — present prejudiced frames when referring to the COVID-19 pandemic, individuals could demonstrate their own prejudice violently, leading to a higher number of hate crimes.

Methods

The methodology for this study was a quantitative approach, focused on the correlation of the variables. The variables in question were the following: a) the total frequency of prejudiced terms found in American news outlets that were extracted from three UNC Libraries databases between March 2020 and June 2020, and b) the total frequency of hate crimes toward the Asian population between March 2020 and June 2020 from the FBI Crime Data Explorer. The prejudiced terms used in this study were “China virus,” “Wuhan virus,” and “Kung flu.” The terms “China virus” and “Wuhan virus” were widely used during the pandemic, appearing in popular posts on news outlets and social media apps, specifically Twitter (now known as X) (Stechemesser et al., 2020). The term “Kung flu” was popularized by the then-president of the United States, Donald Trump, at a rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma, on June 20, 2020 (Los Angeles Times, 2020) and at a youth rally in Phoenix, Arizona, on June 24, 2020 (BBC, 2020b). The term was created as a suggestion that was well received by the audience (BBC, 2020b), along with his insistence on referring to COVID-19 as the “Chinese virus,” on the grounds that China was its place of origin. The mentioned events create a specific frame during the first few months of the pandemic, highlighting the importance of key terms as variables because they are used in news headlines and spark public attention.

Data Collection

The data on hate crime incidents toward the Asian American community was extracted from the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s (FBI) Crime Data Explorer. This website aims to facilitate access to law enforcement data sharing by providing downloads of various files in different formats. Additionally, as a website created by the federal government, its purpose is to expand awareness and accountability in law enforcement, making it an ideal source for data extraction. The charts and visualizations for hate crimes in the United States Incident Analysis on this website provide an organized overview of hate crimes committed in this time range as a whole and by month (March, April, May, and June of 2020). The time range was chosen to provide specific insight into the first months of the pandemic in the United States, starting in March, when confirmed cases spiked, as mentioned previously.

The data on prejudiced terms found in American news headlines was extracted from the NexisUni database (n = 57), ProQuest database (n = 114), and America’s News database (n = 28) and inserted into a ProQuest TDM Studio database, following a systematic count of the terms and providing a total frequency of said terms. Only three databases were selected to ensure precise extraction and data analysis, given the selected time range — ten weeks — for this project and the chosen method for the variables examined. NexisUni, ProQuest, and America’s News database were utilized for their straightforward source extraction and for facilitating searches for news headlines. A total of 199 articles were extracted in the search with the chosen terms found in their headlines.

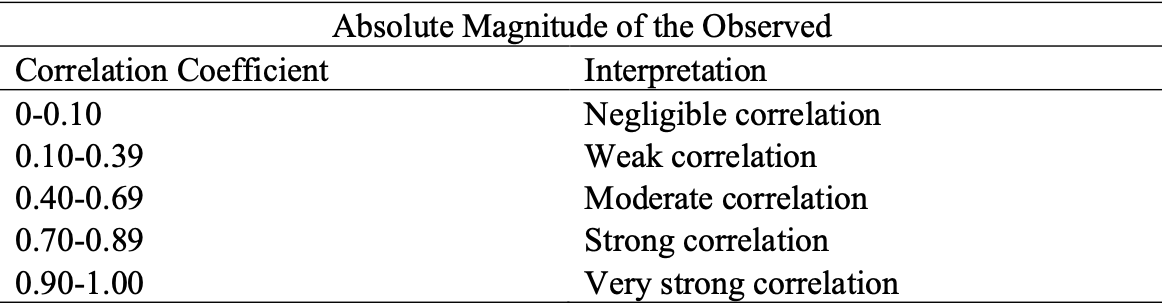

Data Analysis

For statistical analysis, the IBM SPSS Statistics package, version 31.0.0, was used to conduct descriptive analyses and correlation analyses between the frequency of prejudiced terms in the extracted news headlines and hate crime incidents targeting the Asian population. Given the previously specified time limit for this study, the package provided a precise, immediate format for the results and an accessible management of the coded data to be presented. A correlation coefficient is used to find a numerical connection based on continuous data (anything that can be measured) by observing if both variables are in opposite directions (negative correlation) or the same direction (positive correlation) (Schober et al., 2018). This study utilized the Pearson scale for its correlation coefficient because of its bivariate (two variables) nature. A Pearson product-moment correlation, also known as r, is a linear relationship between variables. Said correlation measures the degree of the relationship between the selected variables and exposes how they move together continuously because of its numeric nature. A covariance (an association found in the variability between two variables) is measured through this kind of correlation, scaled between -1 and +1. Figure 1 provides a conventional approach to interpreting a correlation coefficient; this chart is essential to the results of this study and its possible explanations.

Figure 1: Example of a Conventional Approach to Interpreting a Correlation Coefficient

Source: Schober et. al., 2018

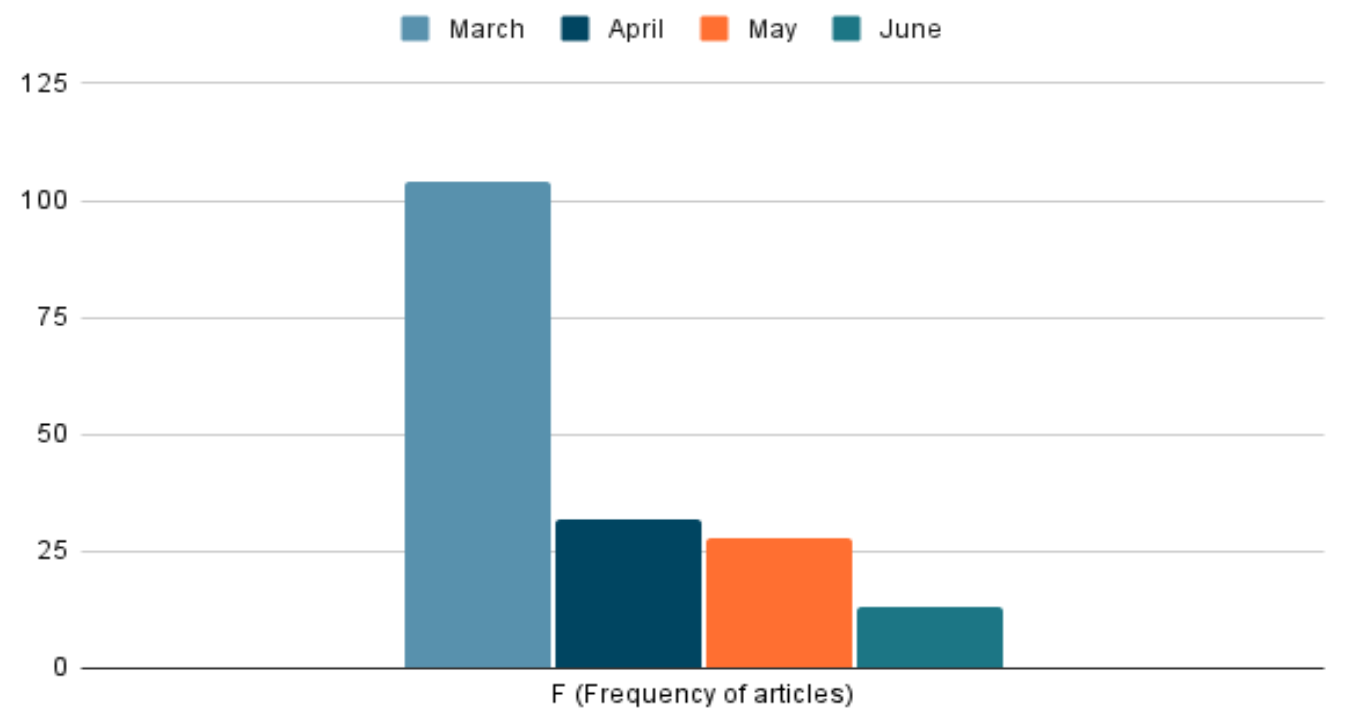

Additional data were provided in this research project to serve as statistical evidence for discussion, such as the number of hate crime incidents per month, which were included in the results section to provide a broader scope of the phenomenon in question. The FBI Crime Data Explorer was used to provide the numerical data. The number of news articles per month from the extracted sources was also presented.

Results

Hate Crimes

The FBI Crime Data Explorer presented 189 reported hate crimes that were defined as ‘Anti-Asian’ between March 2020 and June 2020. Hate crimes toward the Asian community were the fourth-highest amount during this span of time, following hate crimes toward Black or African Americans (n = 1284), White people (n = 347), and Hispanics or Latinos (n = 222). The database presented the Additionally, it did not include the ethnicities that make up the Asian category. This limited the possibility of presenting hate crime reports regarding a specific community within the totality of the Asian population, like West Asians (Arabs, Persians, Greeks, Turks, among others), Central Asians (Kazakhstani, Kyrgyztani, Tajikistani, Turkmenistani, and Uzbekistani), South Asians (Nepali, Pakistani, among others) and Southeast Asians, the last two being the selected communities of study (Chinese, Japanese, Filipino, South Koreans Vietnamese, among others).

Additional data showed the total number of hate crimes committed per month from March 2020 to June 2020. The total number of hate crimes reported in March was 55 (29%), presenting the highest number in the selected range. There was a slight decrease in April, with 51 incidents (27%), while May saw 44 hate crimes reported (23%). June had the fewest reported hate crimes, with a total of 39 incidents (21%).

News Headlines

The news headlines extracted from the selected databases (ProQuest, America’s News, and NexisUni) showed repetition when exported and converted to an Excel spreadsheet. Upon further examination, the duplicate articles were exported because the same articles were published in different media outlets and were counted as individual news articles. A total of 177 headlines were utilized for this study. March has the greatest number of published articles (n = 104), leading to a noticeable decrease in April (n = 32), gradually declining in May (n = 28), and having its lowest number in June (n = 13).

Graph 1: Frequency of news headlines from March 1 to June 30 of 2020

Source: University of North Carolina Libraries, 2025

Correlation of the Variables

The correlation analysis conducted by SPSS determined a positive correlation through a coefficient of r = 0.836. According to the conventional approach to interpreting a correlation coefficient (Schober et al., 2018), this result indicates a strong correlation between the selected variables and supports the previously stated hypothesis.

Discussion

News Headlines and Hate Crime Incidents

Regarding the positive correlation of the variables, the results grant partial answers on reported hate crimes toward the East and Southeast Asian populations; partial because of the lack of sub-categorization of their ethnic groups shown in the Crime Data Explorer. This could mean that the ‘Asian’ category could include populations that could be assumed were not at risk of victimization under the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, like West Asians (Arabs, Persians, Greeks, Turks, among others), Central Asians (Kazakhstani, Kyrgyzstani, Tajikistani, Turkmen, and Uzbekistani), and some populations from South Asia (Asian Pacific Institute, 2019).

The results of this study demonstrate the need to explore numerous concepts and phenomena: the racialization of a minority during the spread of a disease and/or a pandemic; the notion of scapegoating and blame toward a marginalized group (Bae et al., 2022); and the search for empirical evidence regarding the relationship of headlines, prejudiced terms, and marginalized communities, going beyond the East and Southeast Asian population.

Given the nature of this project, the focus on finding a connection between the chosen variables can prompt others to explore it from a different perspective. The positive correlation leads to the possibility of exploring the chosen variables through a causal relationship, organized in the following way: prejudiced terms in news media headlines impact the number of hate crimes toward the East Asian and Southeast Asian population during the COVID-19 pandemic. Although social media use, COVID-19, and prejudice have been explored through a causal manner in previous studies (Croucher et. al., 2020; Stechemesser et. al., 2020; Piatkowska & Wittington, 2024), it is imperative that these variables are explored through other interdisciplinary theories — from social psychology, sociology, media, and American studies — for a rich analysis on this topic, which presents numerous dimensions and intriguing complexity.

Hate Crimes

For this study, the total number of hate crime incidents exported from the FBI Crime Data Explorer was lower than expected (n = 189) when compared to the Stop AAPI Hate National Report (Yellow et al., 2022), which gathered 4,632 hate incidents in 2020 alone, from March 19 to December 31, demonstrating a drastic gap between these organizations. The Stop AAPI Hate National Report was not used for this study due to its broad scope, which could not be narrowed to the selected time range for this project (March to June 2020).

A possible explanation for the low number of hate crime incidents found in the Crime Data Explorer could be the fact that not all law enforcement agencies are required to submit their data collection on bias-motivated crimes (Krishnakumar, 2021). States like South Carolina, Arkansas, and Wyoming do not have hate crime laws (Lieberman, 2025) nor require data collection on these incidents, leading to an unreliable and underreported number of incidents included in the FBI's annual report, known as the Hate Crime Statistics Act. The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC, 2022) states that about 3,500 agencies did not report their data to the FBI for the national hate crimes count and declares that, although the federal agency has been willing to provide support as well as technical assistance for this data collection, many jurisdictions were unable and/or unwilling to take part in the report. Another explanation that should be explored further regarding the low number of crimes reported by the FBI is the complicated dimensions that define a hate crime. Not all crimes are clear-cut and easy to prosecute, as not all perpetrators are overt in demonstrating their racial bias and prejudice. Deep searches into the personal lives of the perpetrators are necessary steps to take when looking for evidence that confirms racial identity and ethnicity as the purpose of the offense (Alfonseca, 2021).

News Headlines

The findings demonstrate that March 2020 had the highest count of prejudiced terms in news articles (n = 104), which suggests that the novelty that coronavirus posed in the United States, declaring a nationwide emergency on March 13 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024), could have led to a ‘blame game’ towards East and Southeast Asian American populations and amplified the likelihood of expressing prejudice towards them as well. Anti-Asian hate has been apparent since the 1800s, specifically over concerns in workplace competition andoverall xenophobia, where the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 perpetuated the label of all Asian Americans as ‘forever foreigners’ (Zhou, 2021). Taking its complex history into consideration, the pandemic exacerbated the preexisting prejudice toward not just the East and Southeast Asian populations, but also the Western, South, and Central Asian populations; this being clear evidence of confirmation bias taking place during the pandemic, as well as complex frames that have been refined throughout history.

Regarding the significant decrease observed between March (n = 104) and April (n = 32), this decline could signal a decision made by the president to use the term ‘coronavirus’ when speaking about the pandemic. Evidence that backs up this claim is an article published by CNN Politics on March 24, 2020 (Vazquez, 2020), stating that Donald Trump “decided to pull back from associating the novel coronavirus with China”, later tweeting that the spread of COVID-19 was not the fault of Asian-Americans (Vazquez, 2020). Another article, published by the BBC on March 23, 2020, supports the argument regarding Trump’s attempt to shift the blame away from Asian Americans, stating that they are “amazing people” and that they will “prevail together” to get rid of the virus (BBC, 2020a).

The findings of this study underscore the importance of examining the entirety of a news headline and its ties to readers' beliefs for future research, as well as observing these variables across other social media apps and through deeper examination of news outlets. Another dimension to consider is the possibility that preexisting beliefs are challenged or modified by what a headline says and promotes, potentially shifting the frame and amplifying the role of the headline's context as a confounding variable. The said variable has been previously overlooked and could influence the independent and dependent variables (Penn State University, n. d.), which could change the outcome of a phenomenon that has been looked into for this project.

Lastly, the duplicate articles further demonstrate the complexity of the findings, revealing the depths of media exposure and engagement through news outlets. Additionally, highlighting the lack of desire to modify controversial headlines, in this case, those involving prejudiced terms, which run the risk of sharing the wrong message with consumers and perpetuating prejudice to create “buzz.”

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

This study focuses on the terms in news headlines rather than the headlines or articles themselves, thereby excluding a significant amount of information that should be examined. The context of the extracted news articles was set aside to obtain precise results on the correlation between the variables. Discourse and content analysis should be conducted in future studies to identify patterns and themes that may emerge. Furthermore, a suggestion for future studies could be a close and comparative reading of articles published from January to December 2020 — the first year with confirmed coronavirus cases in the U.S. — about the COVID-19 pandemic, which could provide a more in-depth exploration of how the pandemic was framed and its impact on the East and Southeast Asian populations. Yu et. al. (2020) explored the connection between different media sources and experiences with discrimination in Asian Americans, making comparative studies even more necessary if they were to be examined with prejudiced terms in news headlines and hate crime incidents. Both of these designs should be elaborated for future endeavors to collect reliable data and provide evidence-based analysis.

The FBI Crime Data Explorer poses another significant limitation to this study, as its counts are less reliable than those in the Stop AAPI Hate National Report, making the desired sample — the East and Southeast Asian population — unattainable for the search for a correlation. The low number of incidents could be explored in future research, which could compare the FBI Crime Data Explorer and the Stop AAPI Hate National Report to assess the trustworthiness of both sources in terms of reporting and their purpose in enhancing visibility for victims.

The chosen headlines are presented as another limitation in this project because a small number of databases were used, meaning the extracted data does not represent the full range of the variable being explored. For future studies, systematic article extraction should include a larger number of news headlines and sources to yield reliable, trustworthy conclusions.

The selected time range poses a significant limitation for this study, as it does not capture the full impact of this phenomenon during the pandemic. The national report by Stop AAPI Hate demonstrated a total of 10,905 hate crime incidents between March 19, 2020, and December 31, 2021. Although the said report does not demonstrate the entirety of the pandemic either, its significant data grants an amplified scope of these incidents. If similar studies were to be conducted in the future, amplifying the time range — from the start of the pandemic in the U.S in 2020 until the World Health Organization’ declaration of ending the public health emergency regarding COVID-19 in 2023 (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2024) — could lead to rich results that could then be compared to previous findings and conclusions, along with their explorations through different methodologies, as mentioned previously.

Lastly, the frequency and concentration of hate crimes by state should be examined, as they were not considered in this study. States with larger Asian and Asian American populations — like New York, California, and Washington D.C. — tended to report a larger number of hate crimes toward said population during the COVID-19 pandemic (Han et. al., 2023 Although this article does not take on the entirety of what makes up the ‘Asian’ population, it elaborates on the geographical ‘hot zones’ of these criminal offenses, how these communities are targets on a larger scale to fall into bias-based incidents, and the increased risk of victimization. Future endeavors could study these elements with other dimensions that contribute to these bias-based incidents, like their locations — rural or urban areas — and the activity of hate groups.

Conclusion

The objective of this study is to determine if there was a correlation between prejudiced terms found in news media headlines and hate crime incidents toward the East and Southeast Asian American populations during the COVID-19 pandemic. The stated objective is partially accomplished. As shown in the results, the lack of ethnic differentiation in the ‘Asian’ category poses a worrisome future regarding the truthfulness and reliability of hate crime counts toward a certain community. The difference in counts between Stop AAPI Hate and the FBI Crime Data Explorer makes the situation more alarming, as it raises more questions about accuracy and the ethnicities included in the federal agency’s results. The observed data presents a clear need for more specificity on the victims as well as the perpetrators, considering it would grant a clearer idea of the realities that different ethnic communities go through, as well as highlight the visibility and transparency of this data collection, so that it can ensure an accurate representation of the affected communities. The Stop AAPI Hate organization is gradually pushing for accessibility to accurate statistics regarding hate crime incidents to increase trustworthiness for future reports and correct representation of Asian Americans (Chan et al., 2024).

Prioritizing the victims' detailed experiences will be vital to a comprehensive understanding of these incidents as well. Knowing their voices are being heard and that there is an ongoing, overt, and real effort to keep them safe will amplify the effect of gradually eradicating hate crime incidents toward these populations and how they are framed through different media outlets.

News headlines have proved to have a greater influence than one might think, demonstrating that their wording determines how individuals approach different events, how they treat the communities assumed to be involved, and how statements made by figures of authority shape their understanding of a significant event. Therefore, these results call for more causal-comparative studies that could explore the effects of news media outlets and provide more insight into how different communities were impacted by their portrayal through these sources during the pandemic, not just East and Southeast Asian populations.

The limitations of this study demonstrate the limitations of using news media outlets as the sole source of data to understand the effects of prejudiced terms. Other media sources, such as social media, newspapers, posters, and billboards, among others, will be essential for future research, especially comparative and discourse analysis studies. The limitations also demonstrate new variables to explore: the examination of hate crime incident cases could grant a greater understanding of the perpetrators’ actions and the psychological dimensions behind them.

The importance of this study lies in the need to explore this model, as well as other methodologies mentioned previously, through other epidemics and realistic counts on hate crimes to investigate trends and elements that could lead to resolutions through public policy and more social awareness of the relationship — and possible impact — of prejudiced terms seen in news media outlets. The COVID-19 pandemic was chosen for this project because it was a global event that affected different communities in numerous ways, making it ideal to explore the correlation among the chosen variables under recent, explicit circumstances. Hate crimes are becoming harder to detect because of covert prejudice and discreet discourse, observed not just in civilians, but in political officials as well. Results and interpretations from studies like this highlight the necessity of utilizing objective words when talking about an epidemic because it could affect anyone, not just through headlines, but in every media outlet. Framing a specific community as the ‘guilty’ one could have devastating effects, especially because of the risk of victimization that comes with it, amplifying the scope of problems at hand. The COVID-19 pandemic, like other epidemics in the past, does not discriminate on the basis of race, socioeconomic status, or ethnicity (Ogolla, 2020); therefore, the limitations presented in this study should be taken into consideration to amplify the ethical dimensions that are addressed when the chosen variables are explored independently or jointly.

References

Alfonseca, K. (2021, April 13). Hate crimes are hard to prosecute, but why? ABC News. https://abcnews.go.com/US/hate-crimes-hard-prosecute/story?id=76926458#:~:text=Without%20solid%20evidence%20of%20hate,problem%20with%20combating%20hate%20crimes.

American Psychological Association. (2023, November 15). Prejudice. https://dictionary.apa.org/prejudice

Asian Pacific Institute. (2019, May 6). Asian and Pacific Islander Identities and Diversity. https://api-gbv.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/API-demographics-identities-May-2019.pdf

Bae, A., Bhalla, K., & Chan, S. (2022, October 11). How political rhetoric inflames Anti-Asian scapegoating. STOP AAPI HATE. https://stopaapihate.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Stop-AAPI-Hate-Scapegoating-Report.pdf

BBC. (2020a, March 23). Trump says coronavirus not Asian Americans' fault. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-52013361

BBC. (2020b, June 24). President Trump calls coronavirus 'kung flu'. https://www.bbc.com/news/av/world-us-canada-53173436

Burke, P. J., & Stets, J. E. (2009). Identity theory. Oxford University Press.

Chan, S., Kang, J., & Castron, B. (2024). The state of Anti-AA/PI Hate in 2023. STOP AAPI HATE. https://stopaapihate.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/09/24-SAH-NationalSurveyReport-F.pdf

Croucher, S. M., Nguyen, T., & Rahmani, D. (2020). Prejudice toward Asian Americans during the COVID-19 pandemic: The effects of social media use in the United States. Frontiers in Communication, 5, 559706. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcomm.2020.00039

Galotti. K. M. (2018). Cognitive Psychology in and out of the Laboratory (6th ed). Cengage Learning.

Han, S., Riddell, J. R., & Piquero, A. R. (2023). Anti-Asian American hate crimes spike during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(3-4), 3513–3533. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221107056

Ittefaq, M., Abwao, M., Baines, A., Belmas, G., Kamboh, S. A., & Figueroa, E. J. (2022). A pandemic of hate: Social representations of COVID-19 in the media. Analyses of Social Issues and Public Policy, 22(1), 225–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/asap.12300

Krishnakumar, P. (2021, March 21). Why hate crime data can’t capture the true scope of anti-Asian violence. CNN US. https://www.cnn.com/2021/03/18/us/hate-crime-reporting-anti-asian-violence/index.html

Lederman, J. (2020, March 25). U.S. insisting that the U.N. call out Chinese origins of coronavirus. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/national-security/u-s-insisting-u-n-call-out-chinese-origins-coronavirus-n1169111

Lieberman, M. (2025, October 17). Hate crimes, explained. Southern Poverty Law Center. https://www.splcenter.org/resources/reports/hate-crimes-explained/

Los Angeles Times. (2020, June 20). Trump calls the coronavirus the ‘kung flu’. https://www.latimes.com/politics/00000172-d4f1-d258-a5f3-fef55e4e0000-123

McWhorter, R. L. (2025). Psychological causes and effects of hate crimes. Research starters: EBSCO research. https://www.ebsco.com/research-starters/psychology/psychological-causes-and-effects-hate-crimes

Meyer, K. (2022, September 26). Incorporating keywords in your news release. businesswire. https://www.businesswire.com/blog/incorporating-keywords-in-your-news-release

Mitchell, A., Oliphant, J., & Shearer, E. (2020, April 29). Americans are turning to media, government and others for COVID-19 news. USA Today. https://www.pewresearch.org/journalism/2020/04/29/1-americans-are-turning-to-media-government-and-others-for-covid-19-news/

Ogolla, C. (2020, April 5). The COVID-19 virus knows no race, no class, no income, or so we think. Center for Civil Rights and Racial Justice. https://www.civilrights.pitt.edu/covid-19-virus-knows-no-race-no-class-no-income-or-so-we-think-professor-chris-ogolla-barry

Pan, Z., & Kosicki, G. M. (1993). Framing analysis: An approach to news discourse. Political Communication, 10(1), 55–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.1993.9962963

Piatkowska, S. J., & Whittington, W. (2024). COVID-19 as a trigger for racially motivated and extremist violent crime: a temporal analysis of hate crimes in Slovakia amidst a global pandemic. Crime, Law and Social Change, 81(1), 99–126. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10611-023-10109-7

Rovetta, A., & Bhagavathula, A. S. (2020). Global infodemiology of COVID-19: Analysis of Google web searches and Instagram hashtags. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(8), e20673. https://doi.org/10.2196/20673

Schober, P., Boer, C., & Schwarte, L. A. (2018). Correlation coefficients: Appropriate use and interpretation. Anesthesia and Analgesia, 126(5), 1763–1768. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000002864

Southern Poverty Law Center. (2022, December 12). ‘Consistently Inconsistent’: Thousands of law enforcement agencies fail to provide hate crime data to the FBI. https://www.splcenter.org/resources/stories/2021-fbi-hate-crime-data-incomplete/

Stechemesser, A., Wenz, L., & Levermann, A. (2020). Corona crisis fuels racially profiled hate in social media networks. EClinicalMedicine, 23, 100372. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100372

Sungil, H., Riddell, J. R., & Piquero, A. R. (2023). Anti-Asian American hate crimes spike during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 38(3-4), 3513–3533. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605221107056

Tavernise, S., & Oppel, R. (2020, March 3). Spit on, yelled at, attacked: Chinese-Americans fear for their safety. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/23/us/chinese-coronavirus-racist-attacks.html

University of Houston (n.d.). What are keywords and why are they important? UH Libraries. https://guides.lib.uh.edu/c.php?g=1249281

U.S. Department of Justice. (2024, July 2). Learn about hate crimes. Hate Crimes. https://www.justice.gov/hatecrimes/learn-about-hate-crimes

Vazquez, M. (2020, March 24). Trump says he’s pulling back from calling novel coronavirus the “China virus”. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/24/politics/donald-trump-pull-back-coronavirus-chinese-virus

Walters, J., Aratani, L., & Beaumont, P. (2020, March 5). Trump calls who’s global death rate from Coronavirus “a false number.” The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/05/trump-coronavirus-who-global-death-rate-false-number

Yam, K. (2020, March 18). Trump doubles down that he’s not fueling racism, but experts say he is. NBCNews.com. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/trump-doubles-down-he-s-not-fueling-racism-experts-say-n1163341

Yellow, A. J., Jeung, R., & Matriano, R. (2022). Stop AAPI Hate National Report. Stop AAPI Hate. https://stopaapihate.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/22-SAH-NationalReport-3.1.22-Final.pdf

Yu, N., Pan, S., Yang, C. C., & Tsai, J. Y. (2020). Exploring the role of media sources on COVID-19-related discrimination experiences and concerns among Asian people in the United States: Cross-sectional survey study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(11), e21684. https://doi.org/10.2196/21684

Zhou, L. (2021, March 5). The long history of anti-Asian hate in America, explained. Vox. https://www.vox.com/identities/2020/4/21/21221007/anti-asian-racism-coronavirus-xenophobia

Esta obra está bajo una licencia de Creative Commons Reconocimiento-NoComercial 4.0 Internacional.

![[in]genios](http://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/51c861c1e4b0fb70e38c0a8a/48d2f465-eaf4-4dbc-a7ce-9e75312d5b47/logo+final+%28blanco+y+rojo%29+crop.png?format=1500w)